Paul Resika

“Then there is a time in life when you just take a walk, and you walk in your own landscape.”

Willem de Kooning[1]

This beautiful sentiment of DeKooning, like his paintings, is meaningful in all its parts. He describes what is the Promised Land for painters, something we all immediately understand, but few actually achieve. It is something like a mystical union that comes only after intense preparation, long waiting, and the ability to see with the “clear light that comes from contemplation.”[2] The union for the painter occurs, not necessarily with the divinity, but when the vision, the materials, the process, forms and space come together with a freedom, directness and clarity that transcends all individual parts and is felt only as experience, as expression, and as emotion.

The time in life DeKooning speaks of is that time when the struggles of youth are overcome and experience has focused the vision. Paul Resika, like DeKooning, is blessed with a long painting life. In concurrent exhibitions at Steven Harvey Fine Arts Projects and Lori Bookstein Gallery we are privileged to see examples of Resika’s work from eight decades, dating back to 1947. At the two shows we can watch the intense preparation unfold and partake in what has been the long contemplation of the artist.

The pictures are expertly chosen by Harvey and highlight different periods of Resika’s career. They do not, however, completely prepare us for the new work at Lori Bookstein. Walking into this space and we are bowled over by large, vibrant, radiant, pictures different in scale and intensity from any of the previous work. He is able to surprise, always curious, always seeking the new.

Paul Resika’s preparation began when he was very young has continued non- stop up to the present. He studied with Hans Hofmann at the age of eighteen and his education has been constant conversation and companionship with the best artists of his generation, as well as the penetrating dialogue he has maintained with the artists of past. The museums and galleries of New York are extensions of his working space, visited for lessons, love and inspiration. As important for Resika is the considerable efforts he makes to visit the shows and studios of younger artists. He learns and draws energy from the art of all ages.

Both his practice and the contemplation begin seriously, I think, with Hofmann. Hofmann taught students to look to nature, not in order to reproduce a likeness, but to transform the rhythms one discovers into pictorial language. It is abstraction, not in the sense of being non- objective, but in the sense of extraction of essentials. The language is that of line, color, and form. Through the decades we see that Resika has always worked this territory.

His relationship with the world of appearances shifts, sometimes closer, sometimes attenuated past immediate recognition, but he is always in this world of abstraction and language. This is what, I suspect, he looks for in the museums and galleries; how this abstract language, learned with Hofmann, is found in the art of all ages.

The effect, or power, of this abstraction, this mastery of the language, is that every part of the painting is elevated to a symbol. Every element lives as both itself, as paint, and as metaphor. The disc can be a vibrant red circle, placed on the picture plane amongst other forms, alive as a participant in the choreography of composition, but it is also seen is also the sign of a setting sun. What is being examined, what Resika has long contemplated, is the nature of abstraction, and conversely, the abstraction of nature. For the artist it is the many ways visual rhymes can be wrought that makes the correspondence.

The poetry of painting is realizing these equivocations that can give rich multiple reading to the art. Such duality, and the artist’s awareness of them, is inherent in titles, particularly in the later paintings. Two pictures are called “Bright Night”. One from 1996 in the Harvey show, the second dated 2012 at Lori Bookstein. The seeming contradiction is belied, or resolved by the paintings, where it is understood that in painting, it is contrast that creates light. The orange pink boats glow against the dark background like the salmon steaks in a Goya still life. In other titles the awareness of metaphor is also apparent. In “Dancing” the rhythm of line is found, and “Pond Galaxy” the rhyme of form, and everywhere, spatial movement through rhythms of color.

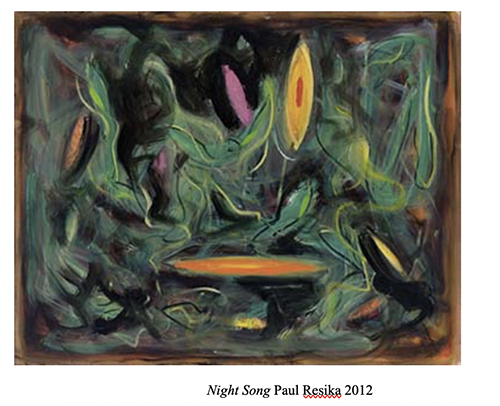

The title of a later painting is “Night Song”. This recalls the name of two of Schubert’s great lieders, set to the poetry of Goethe, Wayfarer’s Night Song, 1 and 2. I do not know if the artist intended this, but there are lovely correspondences here. For Schubert poetry was paramount, and he set his songs to verses that conjure the flora, fauna, and experience of the natural world. The abstraction of music, its language, was used to evoke the rippling brook under the night sky. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, the great interpreter of these songs, stressed the rhythms above all in the music. Likewise, Paul Resika has mastered rhythms, and through the abstract language of painting, evokes an essential experience of the natural world. Fischer-Dieskau was lauded for his art being comprised of equal parts intelligence, deep knowledge of his medium, and emotion. The same can be said for Paul Resika whose long study and intense preparation has payed off. In the work it Lori Bookstein it can truly be said that his time has come, and he, like the wayfarer singing in the night, is walking in his own landscape.

“Nature and art seem to shun each other, but before one realizes it, they have found each other again”

Goethe

Kim Sloane 1/2013

[1] Strokes of Genius: de Kooning on de Kooning (DVD)

Filmmaker: Charlotte Zwerin for Cort Productions

[2] Plotinus, Enneads-Hadot, Pierre. Plotinus of The Simplicity of Vision (Chicago: The University of

Chicago Press, 1993) p. 65

Thanks to my wife, Marianne Gagnier, who read to me a quote by Fischer-Dieskau while I was contemplating this piece.